Globally the share of Electric Vehicles, EVs for short, in new car sales has risen from 4% in 2020 to 14% in 2022, tripling in two years, according to the International Energy Agency. Already in the first quarter of 2023 EV sales are up 25% compared to the same period in 2022. Some estimates put EVs at 20% new car sales market share by the end of the year. In the US, the numbers lag the rest of the world somewhat, however US market share for EVs increased by 55% between 2021 and 2022 from 4% to 8% share of sales. Consumers are clearly adopting this new transportation technology in considerable numbers, and it does not seem to be slowing.

However, are EVs ready for app-based work, like rideshare and on-demand deliveries? In this two-part series, we will look at available data on costs of EVs vs gas powered cars and discover some pros and cons of EVs in the on-demand workplace.

Part Two: Beyond Cost

In our last blog post we looked at the cost of electric vehicles (EVs) and compared them to their hybrid and gas-powered counterparts. EVs clearly represent a cost savings over gas powered but it’s more of a mixed bag versus the hybrids. In this installment we will look beyond cost to the practicalities of driving an EV for app-based work. We will talk about range anxiety, availability of chargers, the opportunity cost of charging, and the difference in delivery and rideshare.

With most new EVs range being around the 250-mile mark, range anxiety is less now than it was just a couple of years ago. However, on a busy day that 250-mile mark can sneak up on you fast, especially if you’re doing significant highway driving where range is lessened. To put it into perspective for Seattle based drivers, you would have to look for charging opportunities after about five or six roundtrips to SeaTac Airport from downtown or South Lake Union. Of course, stopping in the middle of a busy day to charge isn’t ideal, but if most of those 200+ miles had a passenger in your back seat, you’ve likely made $300-$400 at current rideshare rates.

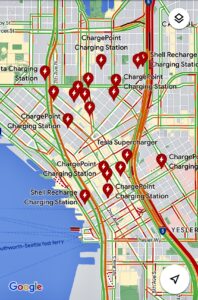

Now if you do have to charge in the middle of your day one other concern many drivers have is availability of public chargers. When looking at google maps, you can see there are chargers scattered throughout the Seattle metro area. In the Downtown/Belltown/South Lake Union area there are dozens of charging stations most with multiple chargers. The same is true if you are out in Redmond near Microsoft’s campus. There are plenty of public charging points near 148th and Bel-Red Road just south of the campus. However, public chargers are less dense near SeaTac Airport, while there is more than a dozen or so however, they aren’t all convenient to the airport. Additionally, as you move further from urban environments public chargers become harder to find so the longest trips may not be suitable for EVs.

Now if you do have to charge in the middle of your day one other concern many drivers have is availability of public chargers. When looking at google maps, you can see there are chargers scattered throughout the Seattle metro area. In the Downtown/Belltown/South Lake Union area there are dozens of charging stations most with multiple chargers. The same is true if you are out in Redmond near Microsoft’s campus. There are plenty of public charging points near 148th and Bel-Red Road just south of the campus. However, public chargers are less dense near SeaTac Airport, while there is more than a dozen or so however, they aren’t all convenient to the airport. Additionally, as you move further from urban environments public chargers become harder to find so the longest trips may not be suitable for EVs.

Also charging while on duty presents another conundrum, if you must stop to charge not only will you be spending extra money to charge but you might be losing money by not being able to take a ride or delivery. Additionally, you may have to decline a lucrative long ride because you don’t have enough battery life remaining. When we spoke to drivers about EVs it was this opportunity cost concern that came up most often with drivers that were hesitating on EV adoption. As one driver James put it, “if there isn’t someone in my back seat then I’m not making money, if I’m spending money to charge too, that’s worse.” It is the limiting factors of EVs like downtime and cost to charge and having to decline certain trips because of lack of range that keep drivers in their hybrids and gas-powered cars.

Photo by Andrew Roberts on Unsplash

However, when we checked in with those drivers that have made the switch to EV, most say they’ll never look back. Uber and Lyft driver Nico used to use a Toyota Camry Hybrid and would spend about $1300 per month on gas, maintenance, insurance, and loan payment. When he switched to EVs he now pays under $900 per month for charging, maintenance, insurance, and loan payment, saving $400 per month. We asked him about the opportunity cost of charging and missing out on long rides, and his said, “I just time the charging for when I’m stopping for lunch or a break. I’ve never canceled a ride because I didn’t have the range.” While he did say he would decline request when they were long rides or long pickups, he qualified that and said he did that too when he drove his Camry hybrid, because he just doesn’t like those trips.

We’ve spent most of this article talking about rideshare, well let’s look at delivery now. It seems that the case for EVs in the delivery environment is clearer. From data we analyzed in our 2021 Delivery Driver Survey most drivers do not drive as many miles as their rideshare counterparts do. In fact, the average delivery driver reported only 616 miles per week, or about 125 miles per day, based on a 5-day workweek, well under the 250-mile range of newer EVs. Delivery, especially restaurant and grocery trips are often much shorter distance than rideshare, so the economics of EVs can work quite well for this type of driving. Additionally, as restaurant deliveries are focused on mealtimes the opportunity cost of taking a break to charge isn’t as great. Plus, nearly every delivery driver we’ve ever spoke to declines long trips as they just aren’t economical in the delivery environment. However, it’s not all good news for delivery, the 250-mile range is only available on the newest models, which can mean a quite hefty car payment. With delivery driving being a very low margin business without the vehicle age restrictions of rideshare, purchasing a much lower priced older model car with good gas mileage may be more cost effective than a brand-new EV.

In looking beyond cost, should you go out and buy a new EV? Well, that is entirely up to you and how you drive, for now. If range still has you nervous and you don’t have access to a home charging station, then a gas-electric hybrid like the Toyota Prius is still the way to go. However, in the next few years significant advances in battery technology, especially in solid state batteries, may change that equation. We would expect that we are still five years away from EVs being the standard for gig-work.

Recent Comments